A Domino Puzzle

I’ve been busy with research and the challenges of job hunting lately, and my brain has been craving some interesting problems to work on. Luckily, I came across a book called Mathematical Puzzles, Revised Edition, which brought me to an interesting problem from Chapter 7 The Law of Small Numbers. After solving this problem, I was also inspired by the idea behind and managed to solve another puzzle I had in mind for a few months. So, I’m writing this blog to share these two interesting puzzles.

A Domino Puzzle

This puzzle is called “Domino Task” in the book. It is described as the following:

An 8x8 chessboard is tiled arbitrarily with 32 2x1 dominoes. A new square is added to the right-hand side of the board, making the top row length 9.

At any time you may move a domino from its current position to a new one, provided that after the domino is lifted, there are two adjacent empty squares to receive it.

Can you retile the augmented board so that all the dominoes are horizontal?

My Thought Process

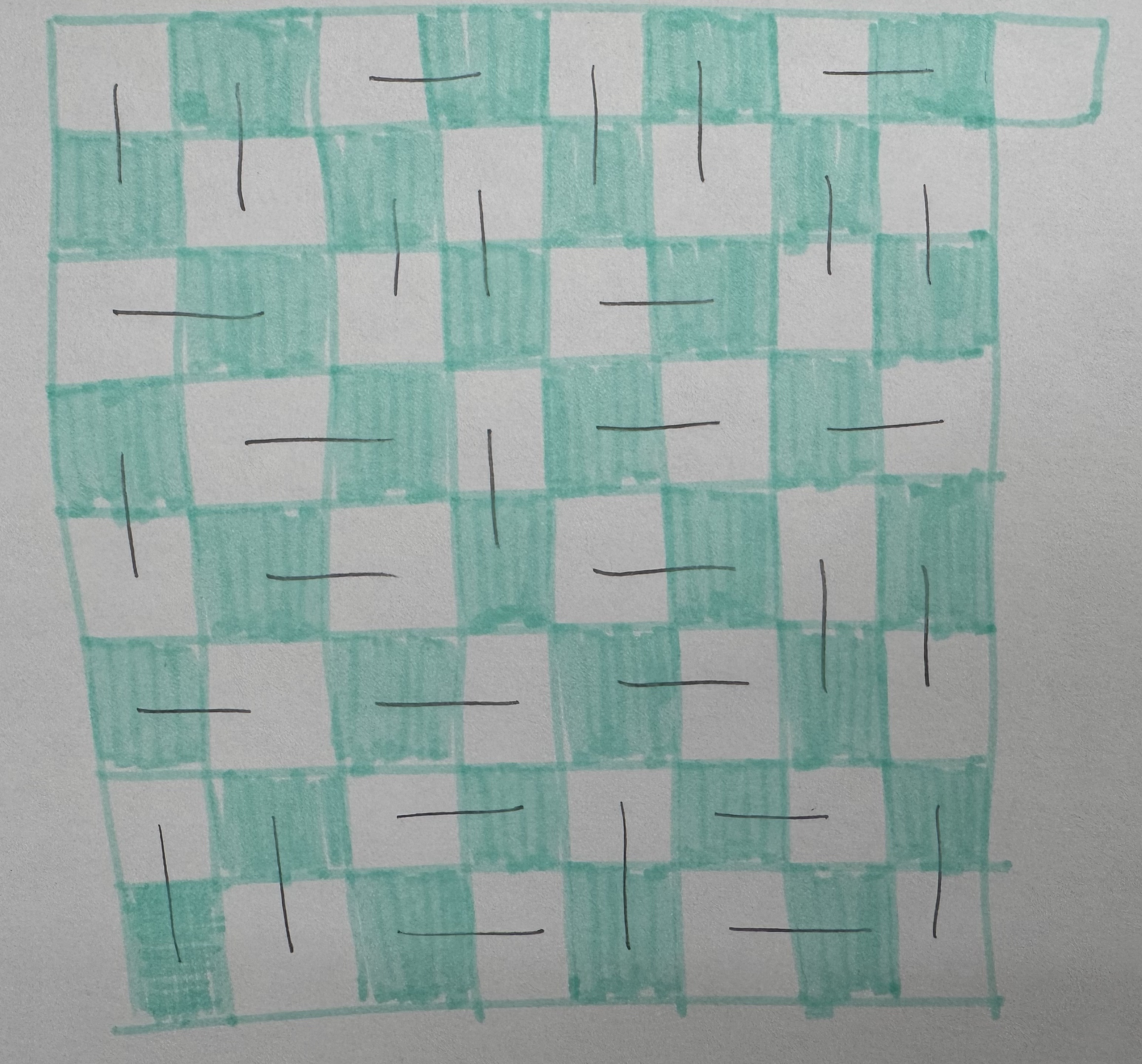

The moving dominoes seemed to be a little bit messy at the first glance. However, notice the fact that each domino always cover one black square and one white square no matter how it’s placed, it is easy to draw the conclusion that each black square is exactly covered by one domino. Further, imagine there is a hinge at each black square, and the domino covering it is rotating on it.

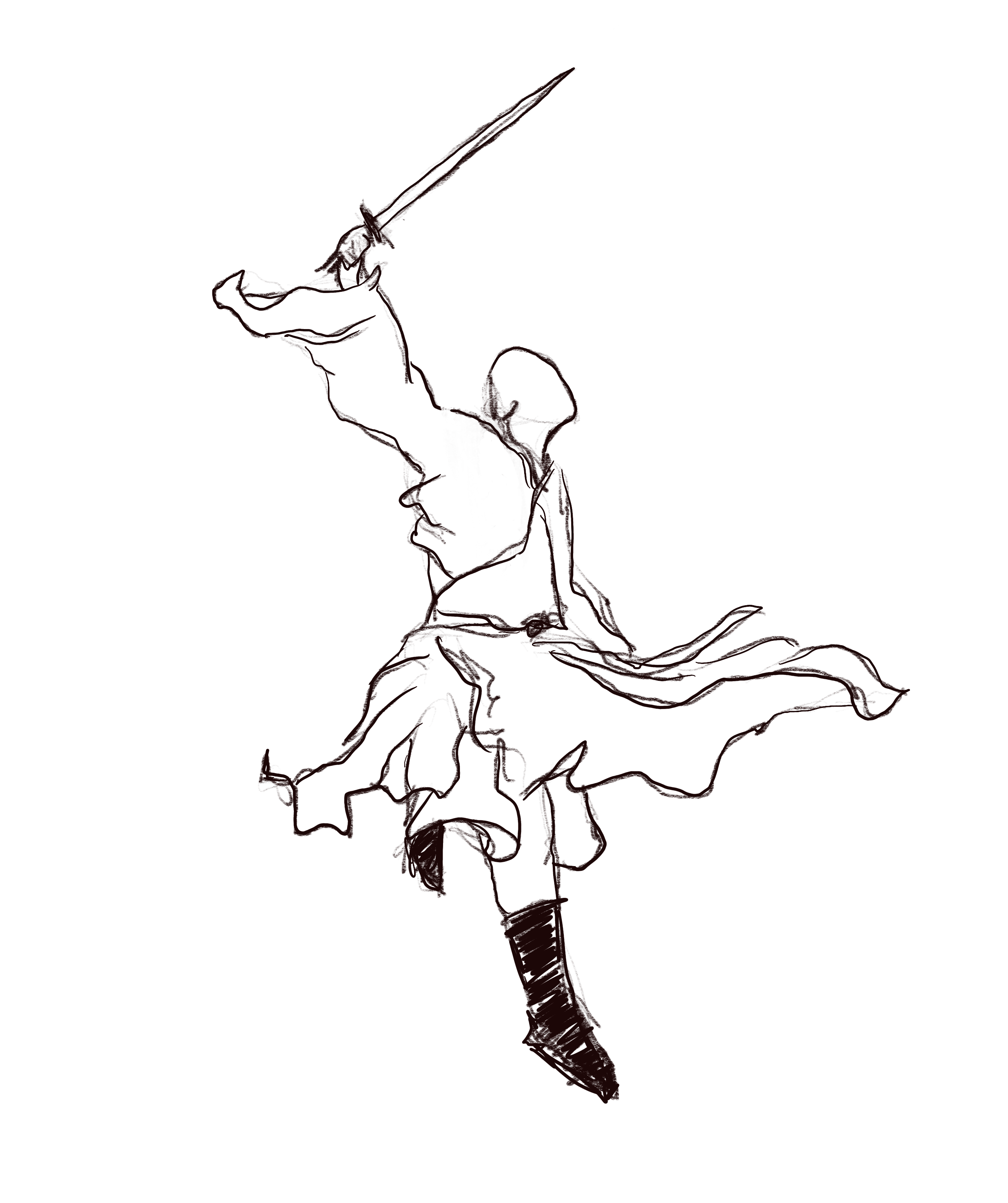

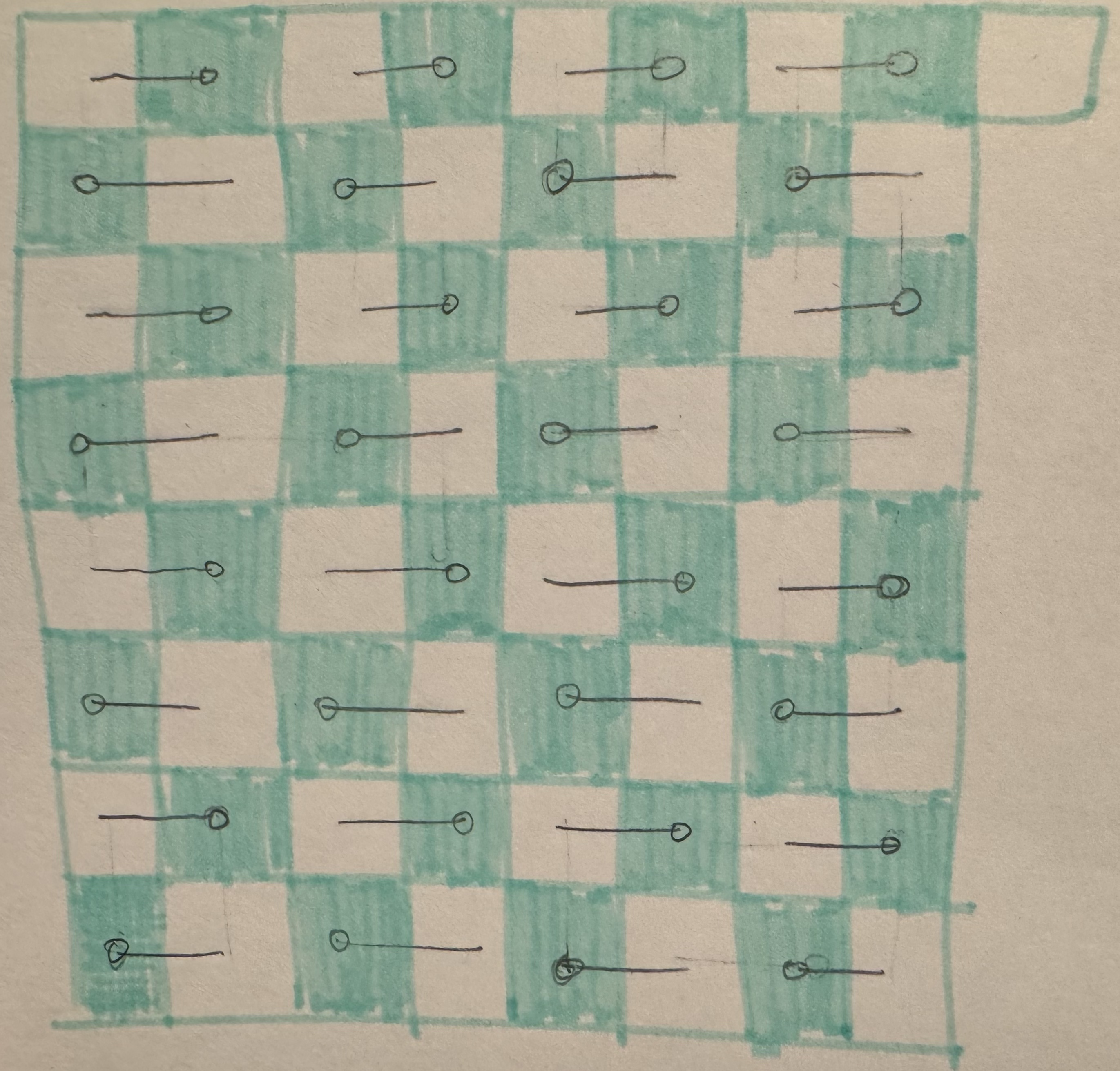

After adding the hinges, the movement of the dominoes appeared to be a bit more “controllable” in my mind. As shown in the diagram above, each piece of domino can have at most 4 possible ways of placement! Compared with the original problem where there seemed to be arbitrary ways of replacing the dominoes, I felt this observation was a meaningful progress.

Next, I started considering the “yes or no” question: Can the augmented board always be correctly retiled? I think it’s reasonable to believe that the correct answer should be “Yes”. I mean, with the hinges by imagination, every domino is at most one step away from its horizontal position, so it sounds pretty achievable.

Then, I thought about how to prove that any given position can be converted to the horizontal one. Usually, there are two kinds of approaches:

- List down a set of clear rules to transpose between states, and prove that it’s always possible to transpose from an arbitrary state to the target state (the horizonal placement).

- Prove that there is an equivalence relation between states, so that no explicit rules are needed and all states can always be converted to one another (this is, of course, a stronger argument).

Further, there are some techinques that may be commonly used when writing proofs of this kind. For example, it may be helpful to have the conclusion proved for a partial problem, and somehow extend the proof to global. I tried to start in this direction, partitioning the 8x8 board into parts like 8x4 or 4x4. However, I later realized that it’s trivial to draw such a partially horizontal placement, in which the dominoes on the lower half of the board are not yet correctly placed, this case shows that it is impossible to solve the problem part by part since the two halves of the board are actually not equivalent due to the extra square on the top right corner.

Since it appears unreasonable to approach the problem using the idea of sub-problems, I decided to think about what might be the last piece of puzzle finishing the construction of the perferct horizontal placement:

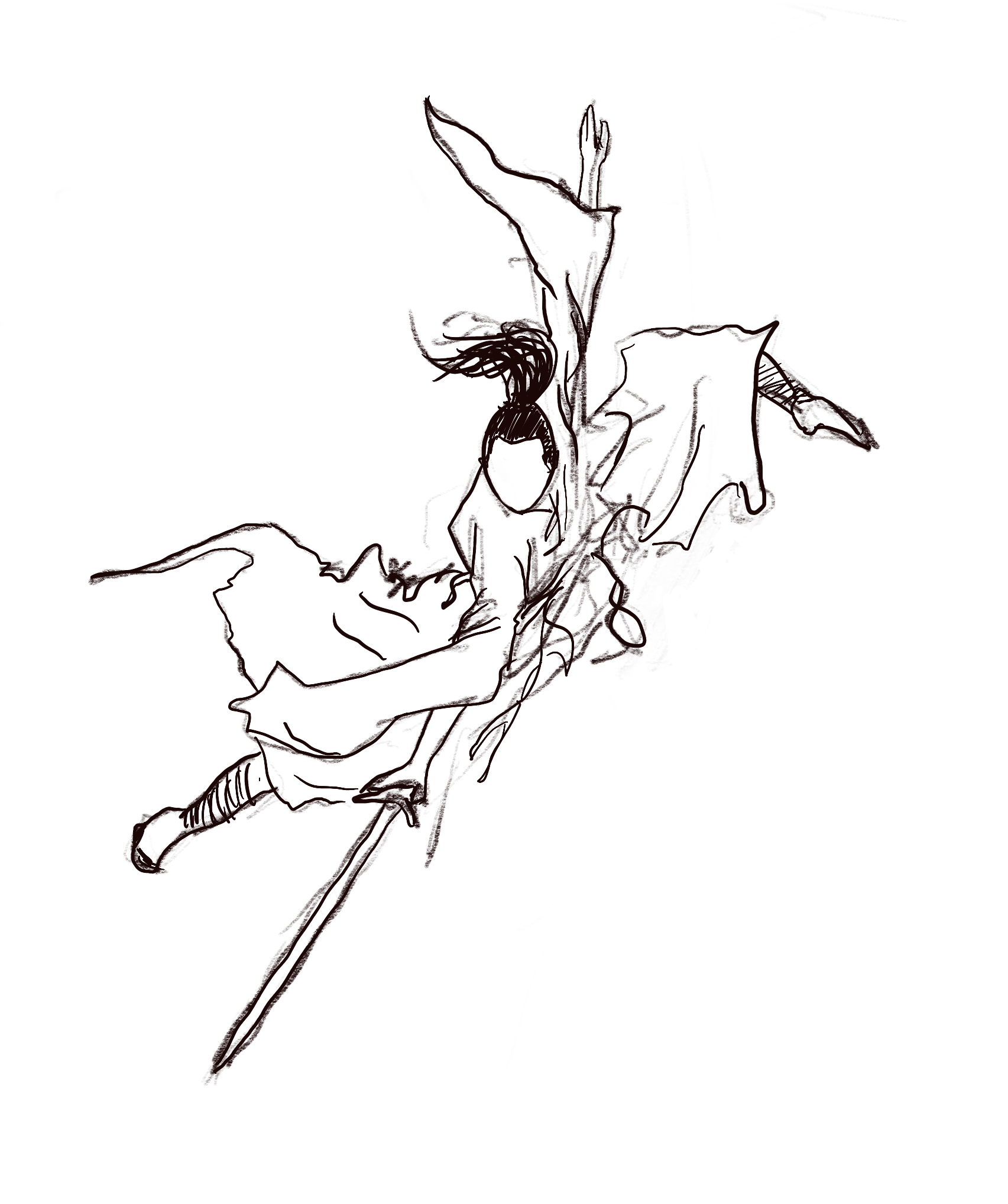

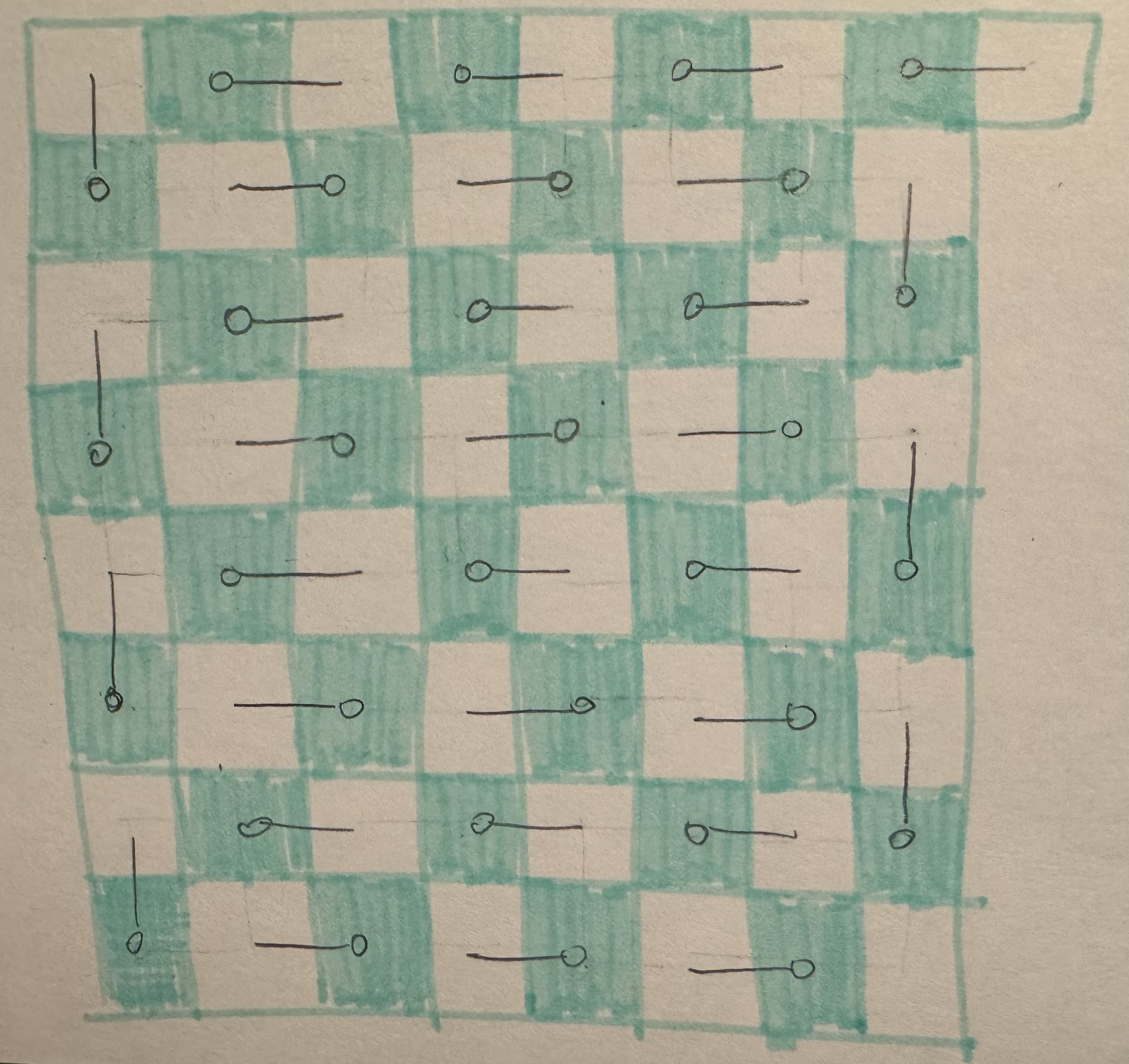

Well, there is actually a trivial answer to this question, since it’s always gonna be the domino on the upper-right corner that got rotated as the finishing piece of the entire construction no matter how the starting position looks like. Similarly, if we go one more step, the second last piece of domino that gets rotated has to be one of the two neighboring dominoes of the upper-right one. Following the same idea, it’s natural to draw the diagram below as a jumping pad for finishing the horizontal placement of dominoes (since one can simply rotate the 32 dominoes one by one from this position to get the horizontal placement!):

Knights on A Chessboard

The idea of “divide and conquer” (or “solving the problem with a smaller number”) of the domino puzzle together with the chessboard reminded me of another puzzle. I remember watching a video clip in which many chess grand masters were asked to answer several puzzles related to chess, and Anish Giri quickly got this puzzle correct (sadly, I couldn’t remember the title of that video).

The puzzle is: What is the maximum number of knights one can place on a chessboard without them attacking each other?

Answer

In the video, Giri quickly arrived at this answer, which was so persuasive that it seemed self-explanatory.

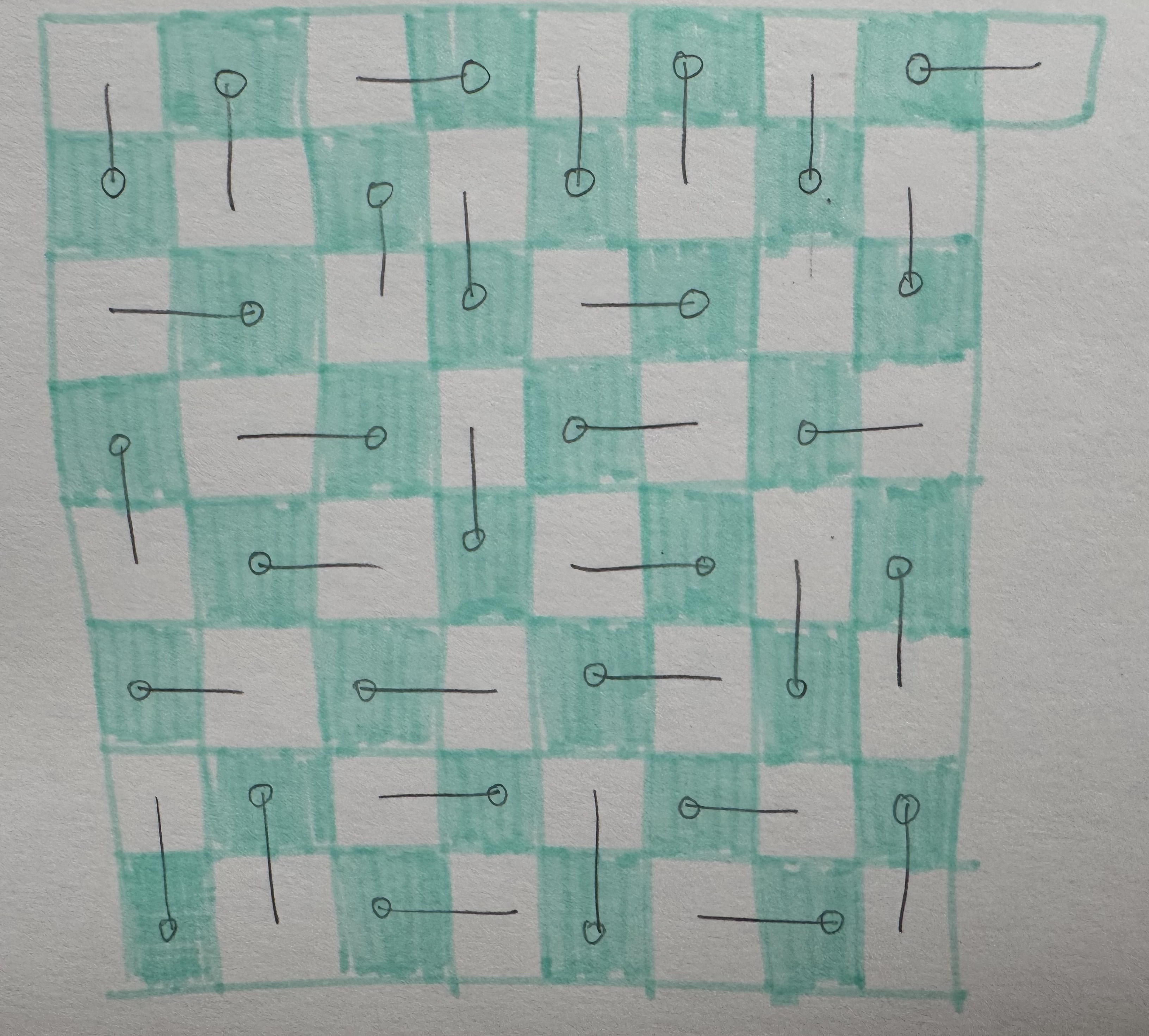

The trivial answer is 32. Due to the fact that knights on the same colored squares won’t attack each other, one can simply place knights all on the dark squares and there are 32 of them.