Paper Review - Leveraging Binary Coverage for Effective Generation Guidance in Kernel Fuzzing

This is a review of the paper Leveraging Binary Coverage for Effective Generation Guidance in Kernel Fuzzing.

Some basic info of this paper:

Authors: Jianzhong Liu, Yuheng Shen, Yiru Xu, Yu Jiang

Published: 09 Dec 2024

CCS '24: Proceedings of the 2024 on ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security Pages 3763 - 3777

Table of Contents

- What are the motivations for this work?

- What is the proposed solution?

- What is the work’s evaluation of the proposed solution?

- What is your analysis of the identified problem, idea and evaluation?

- What are the contributions?

- What are future directions for this research?

- What questions are you left with?

- What is your take-away message from this paper?

Following How to Read an Engineering Research Paper, I tried to summarize this paper by answering the questions below.

What are the motivations for this work?

See Abstract, Introduction, Section 3.

Code Coverage Is Not Sufficient for Kernel Fuzzers

Since kernels contain many untracked but interesting features, such as comparison operands, kernel state identifiers, flags, and executable code, within its data segments, that reflects different execution patterns.

Current kernel fuzzing technologies can only allow fuzzers to explore a less-than-desired amount of the kernel’s code and logic, typically reaching their limits within several days into a fuzzing campaign.

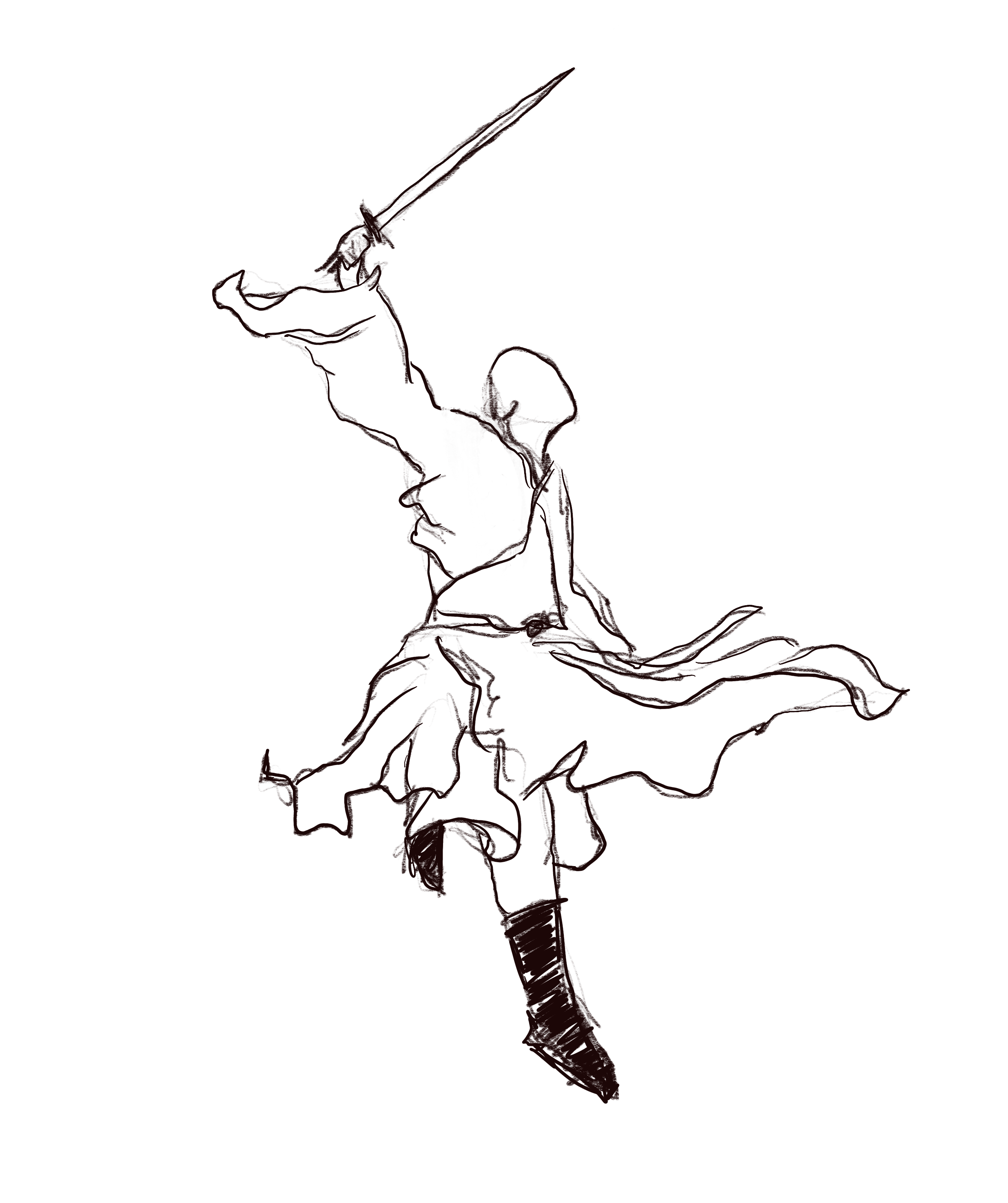

As shown in the figure below, a Linux v6.6.8 compiled to the amd64 target has 43% executable code and 57% data, so adding data to coverage feedback potentially allows 2.3x coverage than pure code-based approaches.

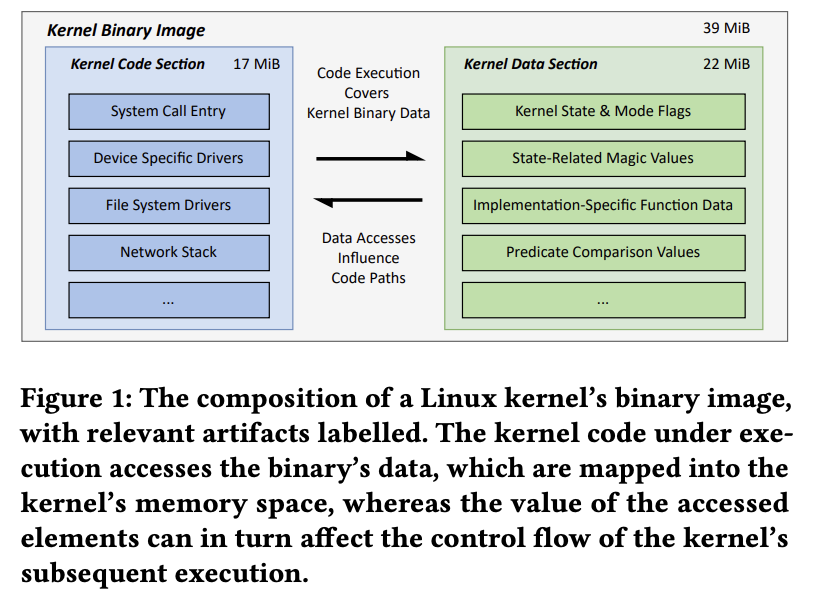

As shown in the figure below, a significant amount of source code for

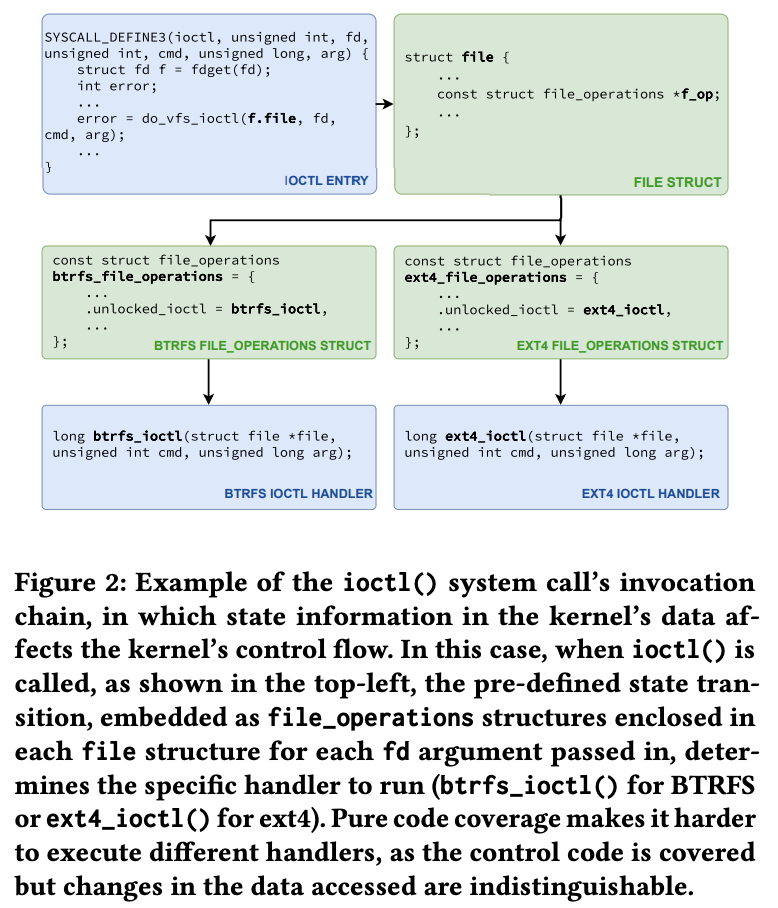

As shown in the figure below, a significant amount of source code for ioctl syscall from Linux kernel v6.9 is compiled to data section, the data stored in member variable of the file structure determines whether a certain handler in code section can be executed. The entry code can be easily covered, but the lack of feedback from the binary data components prevents the fuzzer from identifying differences in the referenced state transition table, thus is ineffective in generating effective request arguments.

Memory accesses to data-relevant features in the kernel binary are indicative of run-time behavior, such as feature and status flags, comparison operands, global objects, etc., allowing the fuzzer to further perceive novel execution traces, thus guiding the fuzzer towards generating more effective inputs, consequently exploring more states and discovering more bugs.

Limitations in Kernel State Coverage

The limitations inherent in code coverage have been received with some research into state coverage, where works attempt to abstract the execution state of the program under test as feedback for fuzzers (e.g. IJON and StateFuzz).

These approaches currently only attempt to model the states of specific variables, as an attempt to represent the running state of programs.

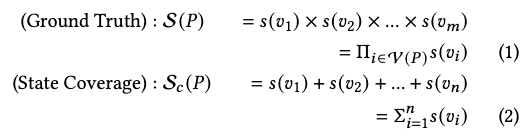

The authors demonstrated the limitation in how current state coverage-based methods captures the coverage with a abstracted view:

Another limitation is the manual labor it takes to identify or specify rules to identify all state-indicating variables.

State explosion, obviously, is another concern.

What is the proposed solution?

See Introduction, Section 4, Section 5.

Key Idea

Abstract kernel behavior as its temporal and spatial memory access pattern during execution. Use this pattern as code coverage metrics.

Optimizations Overview

Optimizations needed for efficient representation of memory access pattern.

- Address approximation for data embedded in instructions (faster, less accurate addr).

- Use static analysis during instrumentation, tracing elision, to remove tracing points that contribute redundant coverage info.

- Filter out variable loads not intended for sections corresponding to the kernel’s binary.

- Multi-level cache-friendly coverage storage.

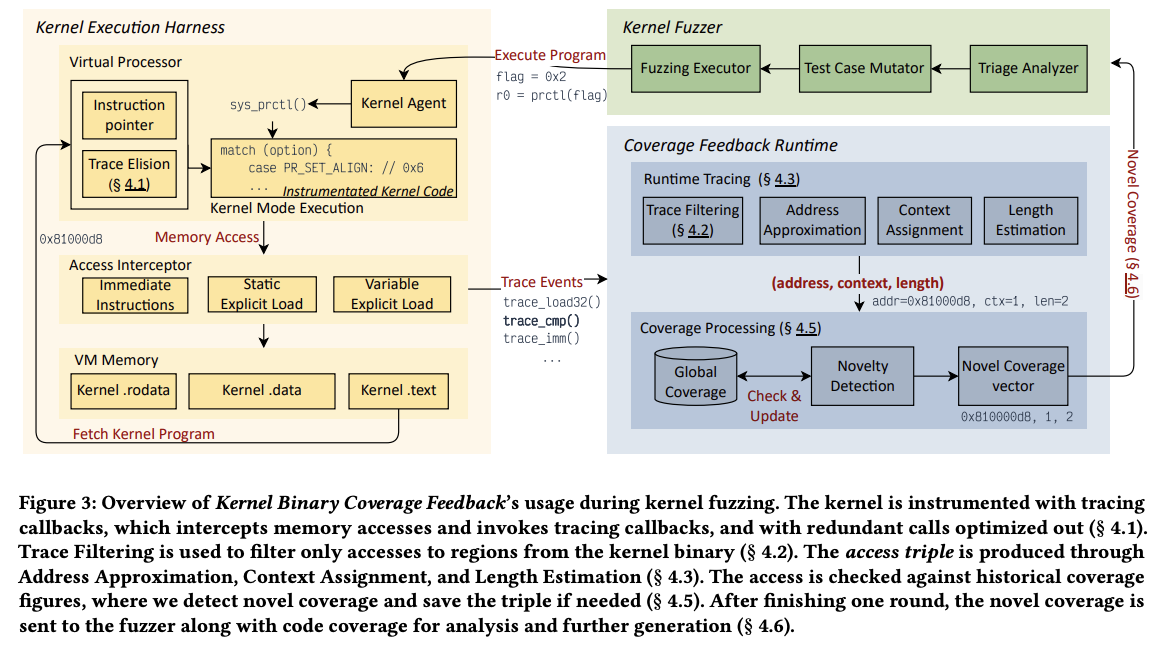

Feedback System

Overview of the feedback system.

Access Interception and Trace Elision

Use program transformation tools that convert the source code into Single Static Assignment (SSA) form, to identify where the static value is directly used.

A two-pass approach involving trace elision is explained in Section 4.1.

Access Pattern Processing

Represent the essence of an access to the kernel’s binary using a triple: (address, context, length).

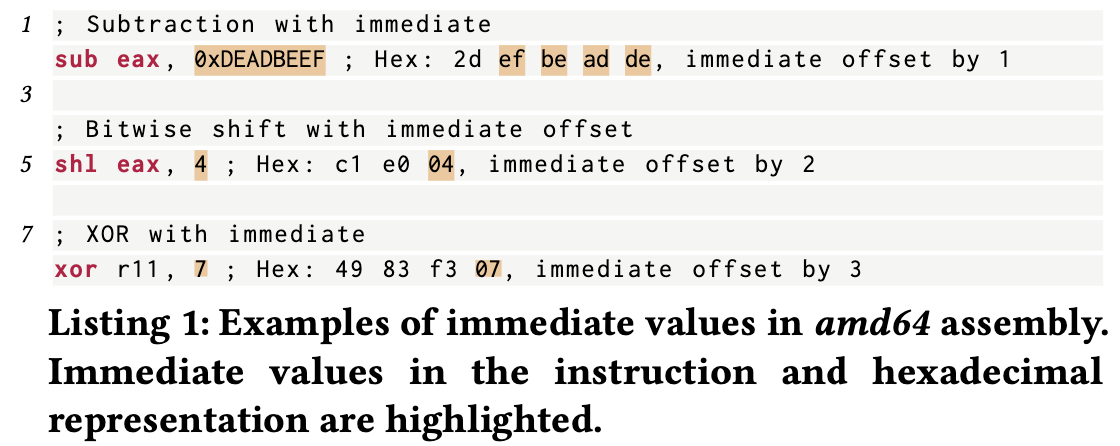

Not all memory access are explicit. For example, immediate instructions access data embedded within the instruction itself, which require specific treatment to approximate addresses that represent the location of this access.

Examples are:

To provide an estimate of the immediate values’ locations, the authors use the address of their embedding instructions as an approximation of their addresses.

Access Semantics

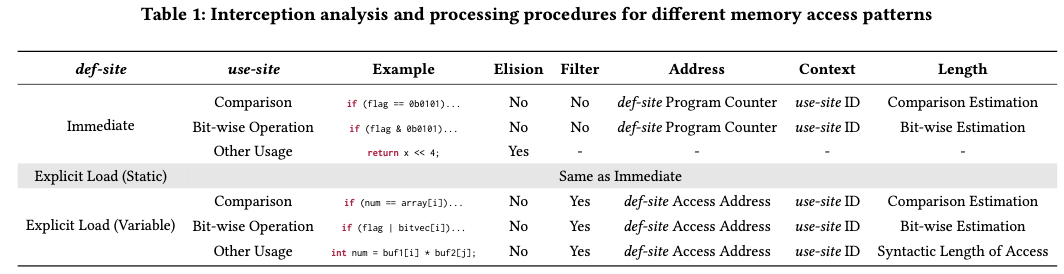

Summarized memory access semantics as the following table:

Implementation

Section 5 covered details of implementation.

KBinCov was implemented upon Syzkaller with QEMU as the virtualization platform. Provided two versions: KBinCov-KVM and KBinCov-TCG.

What is the work’s evaluation of the proposed solution?

See Introduction, Section 6.

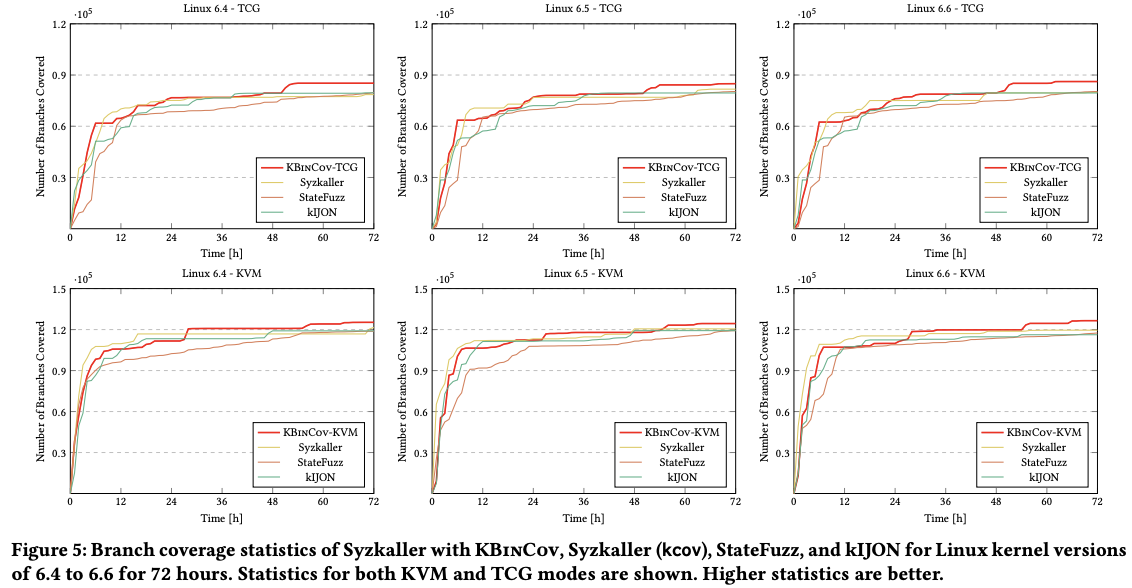

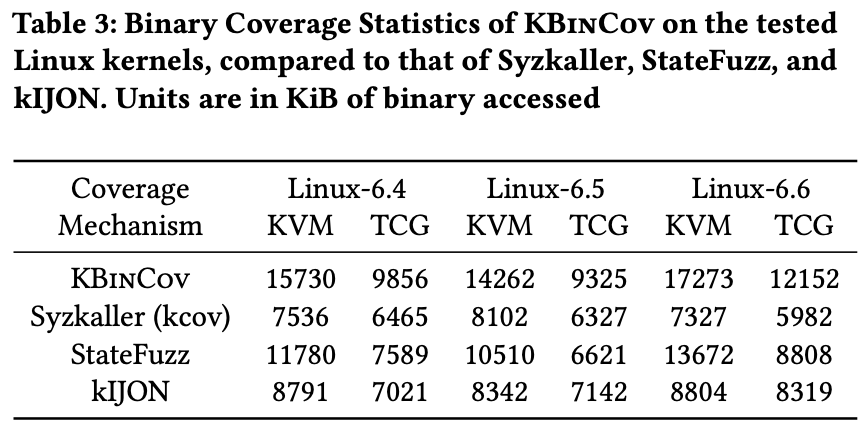

Compared against state-of-the-art kernel fuzzers on recent versions of the Linux kernels. Code and binary coverage increases of 7%, 7%, 9% and 87%, 34%, 61%, compared to Syzkaller, StateFuzz, and IJON.

1.74x overhead, while StateFuzz is 2.5x, IJON is 2.2x.

In Section 6, the authors presents four eval criteria:

- Overall effectiveness in coverage improvements.

- Overall efficiency and accuracy.

- Effectiveness of individual and component-wise design choices.

- Real-world bug detection capabilities.

Branch coverage with KVM gets to an average of 124141 branches on the three versions of Linux kernel.

Binary coverage statistics, with units in KiB.

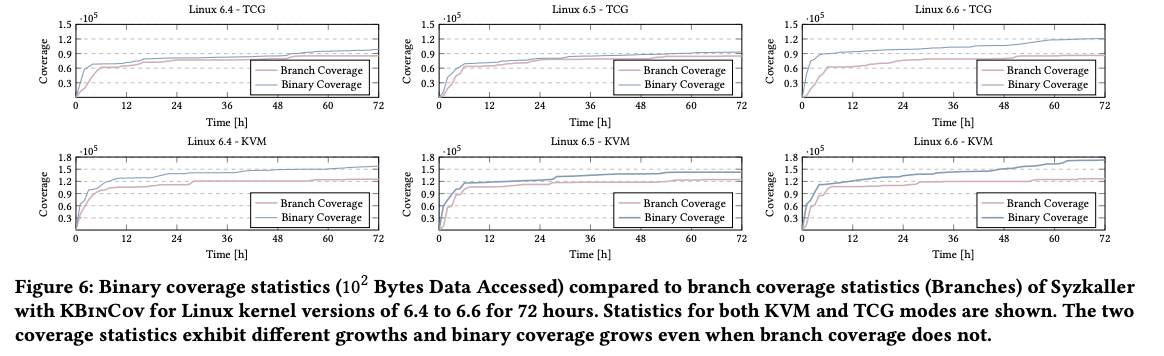

Combining binary coverage and branch coverage.

The coverage experiments are conducted for 72 hours. All bugs listed were found in this experiment. Each experiment was repeated 5 times to reduce statistical errors.

Take-away:

- Both KBinCov-KVM and KBinCov-TCG acheived higher coverage statistics (number of branches covered) than traditional fuzzers as well as state coverage fuzzers.

- KBinCov achieves a significantly higher binary coverage statistic than the comparison.

What is your analysis of the identified problem, idea and evaluation?

The idea of including data access into the metrics is super interesting. I’m a bit concerned about the overhead introduced by data access monitoring, but it seemed to be acceptable according to the experiments. The idea of introducing such metrics is basically provide more detailed feedback to the fuzzer, or, to think of it as manually creating more branches in execution path.

What are the contributions?

See Abstract.

A new execution feedback and novelty detection mechanism, Kernel Binary Coverage Feedback.

A prototype tool KBinCov integrated into kernel fuzzer syzkaller. The tool provides higher code and binary coverage, lower overhead.

Found 21 previously unknown bugs using KBinCov with Syzkaller.

What are future directions for this research?

-

What questions are you left with?

-

What is your take-away message from this paper?

Kernel State Coverage Works

In Section 3.2 the author mentioned works that abstract the execution state of the program as feedback for fuzzers (e.g. IJON and StateFuzz). I haven’t heard of this approach before.

Some Thoughts

Including memory pattern in kernel code coverage metrics can be benefitial as it includes more info.

The memory overhead introduced by memory pattern is affordable, while the run-time overhead might be higher than state-of-the-art implementations. In the experiments, it takes KBinCov longer execution time to really achieve a better result.

In Section 6.2, the authors explained that QEMU-KVM has significantly higher coverage statistics than QEMU-TCG, due to the fact that QEMU enabled a different set of devices under the two modes, thus affecting the number of modules the kernel loads during initialization, and in turn resulting in a difference in the figures when saturated.